Other methods#

There are lots of causal inference methods that I have yet to explore! This page lists some of the methods that I haven’t covered, and goes into detail on a few.

Synthetic control - see below.

Sequential Cox models - [source]

SHAP variants - there are marginal, conditional and causal SHAP values.

SHAP values are usually symmetric, with no causal knowledge incorporated into their calculation. However, Frye et al. 2021(https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1910.06358) proposed asymmetric Shapley values, which incorporate prior knowledge into the calculation. They ‘can be tuned by the researcher to avoid splitting the Shapley feature effects uniformaly across related/correlated features - as is done in the symmetric case - and focus on the unique effect of a target feature after having conditioned on other pre-specified “causal” feature effects’.[source].

There are also causal SHAP values - more on these at source 1 and source 2

Matrix completion - source

Causal discovery - source

Double machine learning - source

Causal forests - source

Structural estimation - source

More on: Synthetic control#

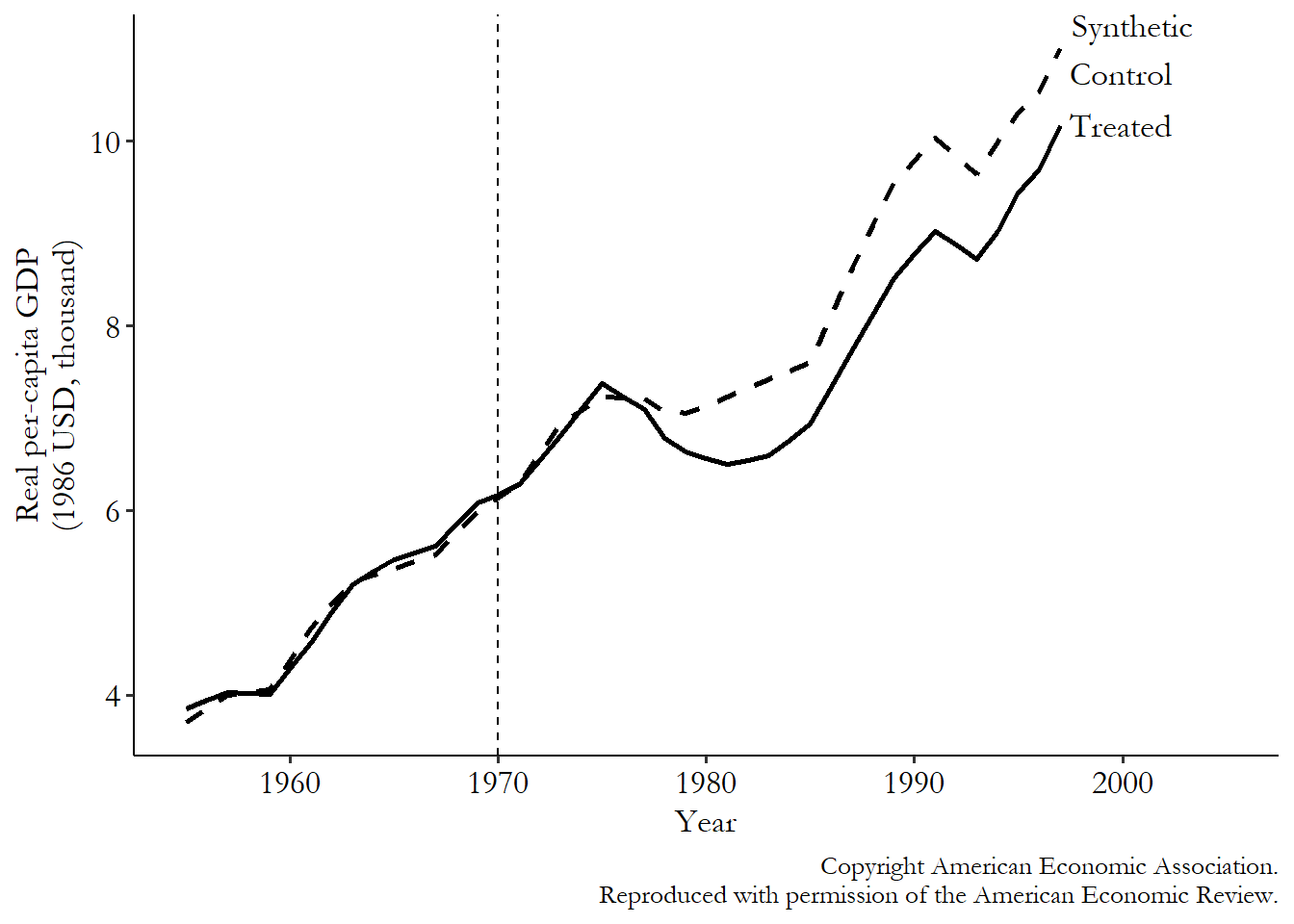

Synthetic control was popularised in Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller (2010). It’s similar to difference-in-differences, although less popular, and requires access to lots of pre-treatment data (‘otherwise the matching quality, or at least your ability to check match quality, will get iffy’)

Steps:

Get ‘treated group and “donor set” of potential control groups’

Matching algorithm assigns weights to each of the potential controls based on pre-treatment data. ‘These weights are designed such that the time trend of the outcome for the treated group should be almost exactly the same as the time trend of the outcome for the weighted average of the control group (the “synthetic control” group).’

Compare outcomes after treatment

Explanation and image from [The Effect: An Introduction to Research Design and Causality - Nick Huntington-Klein]

Comparison to difference-in-differences#

It begins similar to difference-in-differences, but you ‘use data from the pre-treatment period to adjust for differences between the treatment and control groups, and then see how they differ after treatment goes into effect. The post-treatment difference, adjusting for pre-treatment differences, is your effect’.

So it differs from difference-in-differences as:

Pre-treatment different adjustment done with matching (rather than regression like DID), and the matching aims to eliminate prior differences (unlike DiD, where trying to account for propensity of treatment)

‘Relies on long period of pre-treatment data’

‘After matching, the treated and control groups should have basically no pre-treatment differences. This is often accomplished by including the outcome variable as a matching variable’

‘Statistical significance is generally not determined by figuring out the sampling distribution of our estimation method beforehand, but rather by “randomization inference,” a method of using placebo tests to estimate a null distribution we can compare our real estimate to’

[The Effect: An Introduction to Research Design and Causality - Nick Huntington-Klein]